He also met Clavell, who struck him as being ‘a very British Australian’. He had great affection for the producer who he described as ‘short, stout, excitable and great fun’. He flew to Nice where he met Vuille at the Villa Nelleric. Nevertheless, adapting it for the screen would be an exciting writing assignment for Fraser. I’m in partial agreement with Fraser here, Tai-Pan has great spectacle and story, but too often I felt like Clavell was rushing from one set-piece to another with little regard for coherence or emotional involvement. However, when Fraser sat down to read the novel, he found it to be ‘a wonderful atrocity’, ‘turgid and corny’ and ‘supremely dreadful’. Tai-Pan has all the makings of a rattling good yarn as Struan must navigate the politics of empire, ancient Chinese traditions and treacherous fellow traders for the Noble House to ascend to the peak of Victorian mercantile glory. His arch enemy is Tyler Brock, leader of the Brock & Sons company. Dirk Struan is the leader or ‘Tai-Pan’ of the Noble House trading company. Tai-Pan is set in Hong Kong in the 1840’s, shortly after the First Opium War, when rival British trading companies are vying for market dominance with mainland China. Fleischer was set to direct a big-screen adaptation of James Clavell’s Tai-Pan for Swiss producer Georges-Alain Vuille, and he wanted Fraser to write the screenplay. In the late 1970s, Fraser was contacted by film director Richard Fleischer.

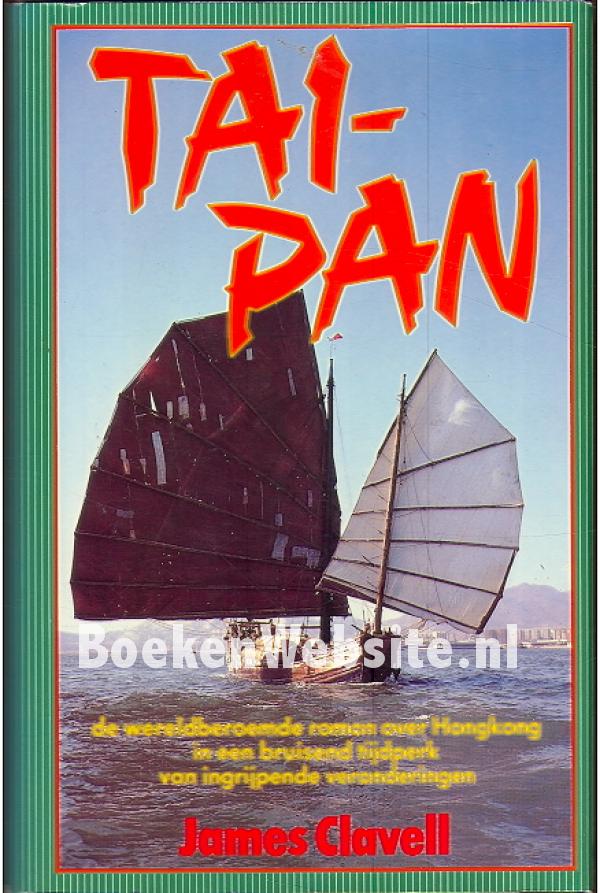

George MacDonald Fraser is best-known as the author of The Flashman Papers, but he also had a prolific career as a screenwriter and his memoir The Light’s on at Signpost covers his time in the movie biz. I am, of course, referring to the big-screen adaptation of James Clavell’s epic bestseller Tai-Pan. The making of this film is a tale of titanic ambition, missed opportunities, horrendous luck, botched compromises and warring egos. I recently came across a film that is the equal to all of the above in terms of never-ending difficulty or, as we might say today, ‘development hell’. I’ve always had a fascination with the concept of a ‘difficult’ production – whether they be unmade films ( White Jazz), forgotten or considered-lost productions ( Where is Parsifal?and The Devil’s Crown), films that weren’t released until forty years after they were shot ( The Other Side of the Wind) or the downright bizarre, how-the-hell-did-that-get-made picture ( Bond director Terence Young’s cinematic love letter to Saddam Hussein is a notorious example of this genre).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)